Toposomatic Inheritance

Laken L. Sylvander

1

2

3

3

4

5

6

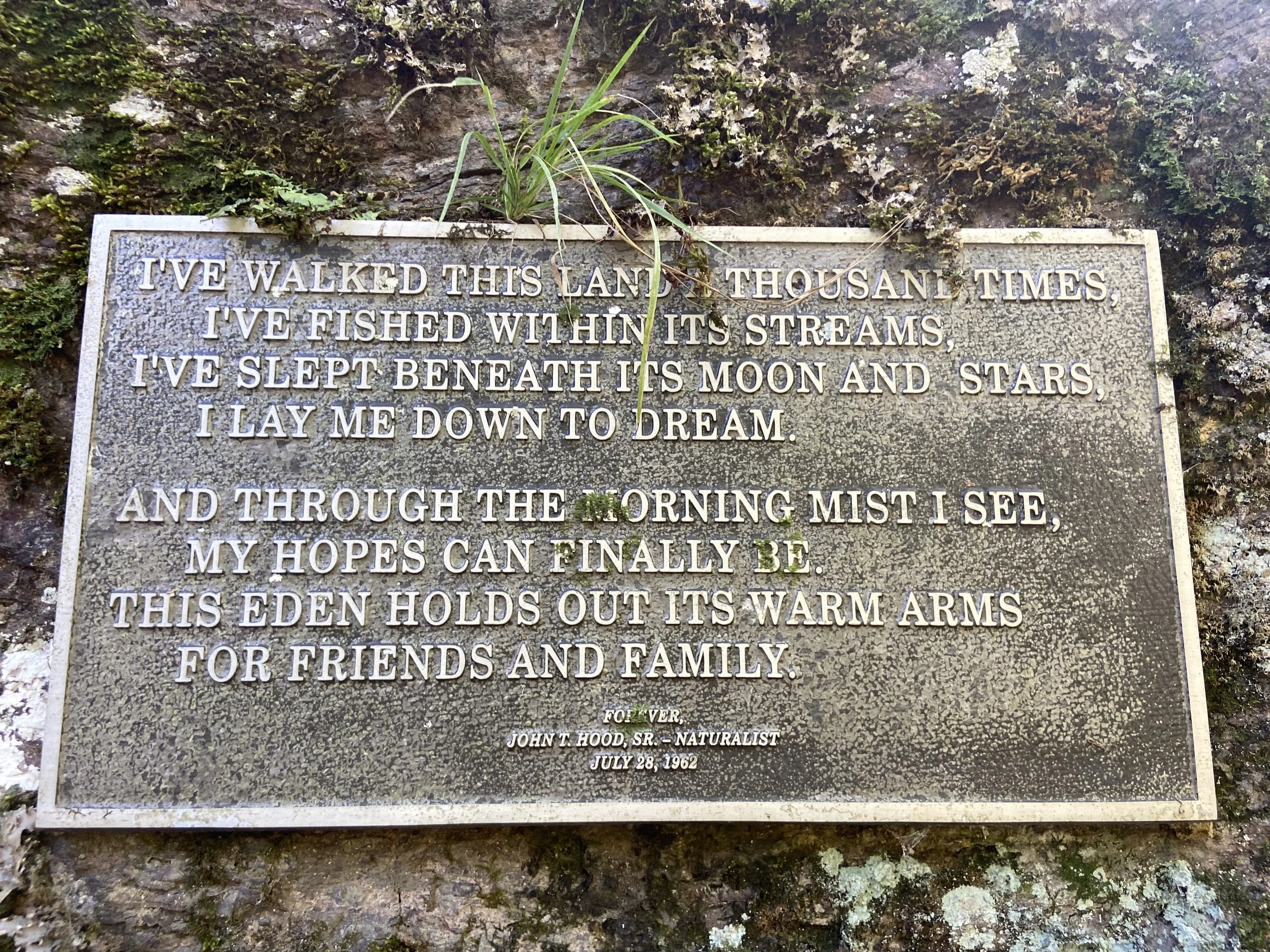

Bronze plaque installed at Marble Creek in memory of John T. Hood Sr., artist’s maternal grandfather - Black Mountain, MO. Poem by Laurie Greer, artist’s maternal aunt. Plaque installed and photograph taken by a family member in 1998.

The same plaque photographed in 2024 by the artist.

The front of the Toposomatic Black Mountain Coat, hung from a tree in the artist’s grandmother’s garden in St. Louis, MO.

The artist’s grandfather, John T. Hood Sr., stands at Marble Creek in the late 1970’s.

The back of the Toposomatic Black Mountain Coat.

The artist wears the Toposomatic Black Mountain Coat.

The artist’s maternal family gathers for the installation of the memorial plaque at Marble Creek in 1997. Artist is on her father’s shoulders, top left. The artist’s childhood dog, a husky-mix named Korki, is in the foreground.

Place-Body: Dressing the Topo-Soma

With “Toposomatic Inheritance” I offer a tangible approach to future inheritance of place and body through the construction of garment.

The Black Mountain Toposomatic Coat (topo - place, location; soma - body) is an experimental garment meditating across constructions of heritage, colonial ancestry, environmental violence under capitalism and 'rights' to place through private ownership and inheritance. It is accompanied by a poem from the vantage of my passing the coat down to future inheritors - not inherently biological descendants - in the year 2075, recounting my own memory-keeping of the land and speculatively addressing how ownership and collective stewardship have changed across my lifetime.

We link place with body all the time - coordinates and maps are tattoo’d on skin, we wear gemstones harvested from near and far in our ears, around our necks and fingers. Too often, contemporary people are far removed from the places that make their everyday Earth lens: our clothes.

In the Black Mountain Toposomatic Coat, topographic mapping’s human-oriented navigation encounters the medium’s technocratic insistences and certainties: the rendering of nature as hyper-legible for the purposes of consumption, as capitalism demands of our contemporary relation to the natural world. The core problem with assuming legibility, and thereby extractability, is that maps aren’t static: topography isn’t static because water levels are not. Therefore, mountains aren’t static as Western thought would have us presume, and yet Western systems are those forcing water-level changes.

This conceptual-functional garment plays with unraveling the human-made certainty of the natural world, while distorting my own knowing of place, and letting both the topographies of this textile and my own body embed a re-rendering of the topographic lines of Black Mountain, Missouri, rejecting hierarchy and linearity of color so as to make the place illegible. This coat, hand-crafted onto my body from an original pattern, is constructed from a textile made of recycled water bottles known as eco-fi felt. Once constructed, a topographic map of Black Mountain, Missouri, was projected and traced onto the fabric. I then deconstructed and reassembled the coat along the map's lines, creating a patchwork assemblage of an intentionally inaccurate - but loosely identifiable - map. Each piece of the deconstructed garment was hand-dyed to obscure the topography’s precise legibility.

Through this artifact of construction, deconstruction, and assemblage, I question what it means to know — and inherit— place. My maternal grandfather owned and passed down land in the Black Mountain region to his children, thus I feel a responsibility to explore the possibilities of passing down place-memory through garments and oral histories rather than private land-ownership. In consideration of how the Land Back movement demands urgently-needed changes in natural resource stewardship, this conceptual garment imagines land and body stewardship as healing in a future where the place-body (topo-soma) and the ephemeral yet tangible work of memory-keeping and place-making exist in harmony with the Earth system.

Laken L. Sylvander

This work gives me hope after a long period of climate pessimism.

The Topographic Black Mountain Coat is one experiment in bringing critical theory to material life, confronting heritage, extractive capitalism, and my own fascination with garments as lenses between body and environment. I take very seriously what I have inherited - materially, biologically, environmentally. I want my work to inspire white Americans especially to consider how consumption and colonial legacy shape our everyday lives, and the privilege we have to accelerate the pace of shifting away from the economy and culture of resource extraction and corruption that our people have created.

I am perpetually bouncing between mediums. I have spent years deeply immersed in music production and songwriting, and spent even more time as a dancer in my childhood, adolescence and early adulthood until injury detoured me towards the more sedentary medium of producing music electronically. I paint to meditate and do yoga to feel back in my dancer’s body. I grew up in big cities and now head to the woods or the lakeshore as often as possible.

As a daughter, older sister (to a brother and two beautiful dogs), granddaughter and artist, relationality guides much of my approach to my advocacy work and artwork - inheritance in all directions, human and non-human.

I am intrigued by the present opportunity that modern Americans have to understand colonial history with more access to our own part in it than ever - especially from my perspective as a descendant of white colonizers of this land. People young and old are sending in their DNA to get back results of their ancestry and getting vast amounts of information - but what are we to do with this influx of information otherwise lost to time (or to violence through historical oppression)? My work exists to make sense of the urgency I feel to encounter the colonial forces that landed my body in the United States. As an extension of that colonial lineage, I feel even greater urgency to restore symbiosis with the natural world. I respond to this internal urgency, paired with an open and honest reckoning with historical violence of capitalist systems on the environment, through music, poetry, and academic work.

In 2021, as I began to emerge from an pandemic-induced sabbatical, the critical readings I had spent so much time with in 2020 took form, unexpectedly, in garment creation - a medium I found myself returning to for the first time in many years. The materiality of consumption, and confronting my own consumption of clothing and textiles especially at this time, lead me into deeply-burrowed rabbit holes of researching natural resource extraction and pollution. I discovered Eco-Fi felt, which the Toposomatic Black Mountain Coat works with. I also ordered a bag of leftover reptile skins from a leather tannery in Kansas City, MO from their “scraps” sale; when it arrived, I was stunned to see the small cut-outs of iPhone case shapes and passport sleeves amidst the massive amount of animal skin “waste.” I was inspired to transform those skins into bags with the cut-outs exposing the contents of the bag. My obsessive reading and research on consumption invited the medium of clothing design, and I’m excited by the potential of molding materials to bodies, weaving resources and histories.

I intend to continue experimenting and creating with these small efforts to waste less within the demands of textile consumption, while foreshadowing this effort with advocacy for resource defense systems and land back movements to see a 2075 that I would like to leave to future generations to steward.